In any shape it may appear, gold provokes, it raises interest, and sometimes it may even lead to obsession and make you its slave. You can’t even tell what draws you to it, because, in truth, it’s good for nothing, it’s not vital. Perhaps it’s about its beauty or the fact that you can make something beautiful out of it, you can polish objects or make jewels. It can mask ugliness or mere banality, because it’s clean, it shines, it’s got light inside. Beautifying and falsifying are equally in its powers.

Gold has its own personality, and this is why it’s fascinating and domineering. It is diurnal, franc, without hidings and shadows, it is consistent and impressive. It imposes respect and a certain distance. It cannot be a vassal, it cannot be shadowed, and it does not have the lucrative deceitfulness of gray eminences. Gold is charismatic; it radiates and shines by its mere presence, without effort, rhetoric or theatrics. It makes you appreciate it, want it, and fear it all the same. If you get too close, you risk getting burnt, but if you keep your distance, you can rely on it.

We now have an “ideological” obsession for gold. It is the substance left from a Paradise we were driven out of, and with which we want to polish our fleeting lives. We want to coat the world in a golden powder to remind us of that happiness, and to make the sadness of being cast away bearable. It’s why we speak of a Golden Age, a golden crown, a golden cup, a gold medal, a golden boot, gold rings, or gold teeth. From king to chav, and from sport champion to fiancé, they all have a connection to gold. Someone proudly wears on his head a noble crown setting him apart from the rest of the world, a world that, from that moment on, bows to him in obedience, someone else grins stupidly through uneven lips to let his gold teeth sparkle. Someone triumphantly raises in the air the golden boot that makes him the best football player of the year, and another one, the gold ring on his finger placed there by his new wife. Each of them associates gold with a performance or an important even in their lives. Gold has become the measure of human qualities, performances, and events.

Gold’s domineering force, in direct proportion with the will to have it and the energy invested in having it, is both physical and psychic. It would be more appropriate to call it magic. Thus, something close to erotic passion fuels our relationship with gold. The association of gold with the object of love, and its transformation into a metaphor for all that is precious in life have become commonplaces: for a parent, his child is golden, for someone who is in love, the beloved is made of gold, there’s a gold stone that can make one immortal for the philosopher and the alchemist: the sovereign, through his golden crown, part of the royal attire, acts like the Sun God, master of the universe.

The common man, the poor, to whom life hasn’t offered anything that could be appreciated through its relation to gold, is left, nevertheless, with the fairy tales: golden birds (Der Goldene Vogel, the Brothers Grimm), girls with golden hair (Calin Gruia), the golden cockerel (Pushkin), the gold key (Tolstoy), golden apples, the golden bough (mistletoe), Prince Charming with golden hair (Petre Ispirescu), the golden garden and many others. There’s almost no fairy tale, legend, myth or epic where gold is not present under its many faces, with its insidious way of taking over our sensibility. If the gold in nuggets, in coins or bullions, in jewelry or decorations is limited, hidden in the mountains, shown in museums, deposited in banks or ostentatiously exposed in jewelry and accessories, the fairy tale gold can belong to any one of us; it is unlimited. This is, probably, the real gold, that it to say, the equivalent of gold in spiritual life.

Since its discovery thousands of years before our time, gold has become not only the most precious asset or material for ornaments, but also the highest symbol of goodness, beauty, power, happiness, love, hope, optimism, intelligence, justice, perfection. Mysterious and hypnotic, gold seems to have gathered together all the properties, all the qualities and virtues tied to the sense of nobility and the cult of human greatness. Science is no stranger to it, either, since it named one the most beautiful mathematical discoveries, the irrational number, “the golden section”. Gold is sought after because it remains, beyond its many metamorphoses, an instrument of power and a source of domination, even in the form of accessories. Cleopatra’s dress, embroidered in gold, is an instrument of power as well.

Traditional technologies for obtaining gold

It is clear that the symbolic importance of gold, on the one hand, and its economic value, on the other hand, contributed to the continuous improvement of the methods used to extract it and of the processing technologies. No matter how poetic and picturesque were the sheep or goat skins used for a long time and in many places by gold prospectors, they couldn’t guarantee a quantity as large as the prospector’s gold rush. The sheepskin could catch fine particulate gold dispersed in river water. Sometimes, for maximum efficiency, the skin would be burnt, which melted the gold, making it easier to work with. It was a method somewhat similar to fishing, limited to taking out of the waters the little gold which could be found in some rivers. The grinder and mortar, used as primitive technologies for the extraction of gold from rocks, were not only difficult, but they also required a huge human workforce, all with unspectacular results.

In order to extract gold from sands or rocks, especially in the places where mining already existed, new technologies were needed. The invention of the stamp mill (stampf in German) was an extraordinary progress; the technology behind it was quite simple and it was easy to use on riverbanks. In the areas from the Apuseni Mountains rich in gold, such installations started working when mining was taken up again after the Roman retreat, when it was briefly interrupted. The German peoples colonized in Ardeal by the kings of Hungary starting with the 13th century will then contribute to the development of mining, particularly to the extraction of gold in the mines from Apuseni.

The stamp mill facilitates crushing, grinding and selecting the gold from the rock by using water force. Usually, stamps were placed on riverbanks, in places bought or inherited by a single individual or a family, and sometimes they were placed near waterfalls, to maximize the water drop. The ore is poured into the basins at the base of the stamp and then crushed by the “arrows” launched rhythmically by the hydraulic wheel through a horizontal spindle. The non-linear arranged pinions in the spindle touch, when the spindle rotates, the arrows, causing them to fall and forcefully strike the ore, crushing it with the stones in their top ends, provided with iron rings. The ore is then conducted by the continuously flowing water into a large basin. Since it is heavier, the gold deposits at the bottom, from where it is later removed and cleaned. The remaining gold particles left in the tailings deposited in the basin are then recovered through by washing the material on a wooden board at an angle, covered in a thick woolen cloth. The golden sand thus leaves behind golden grains, while the ore residues are washed by the water. Again, the thick woolen blankets seem to resemble the ingenuous archaic sheepskin.

As they depended on the water, the stamp mills had to stop their activity in dry periods and in wintertime, when rivers froze over. The best working period was between mid-March and November, depending, of course, on each winter. In the second half of the 19th century, Californian stamp mills were introduced in the mining in Apuseni, at Rosia Montana as well. Their metal arrows were much more resistant, more efficient and more reliable than the wood ones used by prior technology, which made their use frequent in gold mining all over the world. A few decades ago, after World War II, they were still functional. Their main advantage was the fact that, being run by electrical or steam engines, they could be active all throughout the year, unrelated to winter weather and river flow.

Gold sources

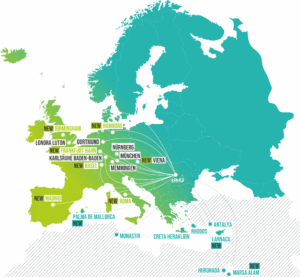

Romania’s richest gold areas were Maramures and the Apuseni Mountains, the so-called “Golden Polygon”. In Maramures, native gold deposits could be found as gold filaments or strands in the mines at Baita, Sasar, Valea-Rosie, Dealul Crucii and Suior. The filaments in Baia-Mare region were 1,000-2,000 m long, running up to a few hundred meters deep, with an average concentration of 2.2 g Au/ton of ore, up to 4.5 g Au/ton. The area of the Metaliferi Mountains, between the rivers Aries and Mures, where the Gold Polygon of the Apuseni Mountains is located, had gold deposits at Baia de Aries, Zlatna, Sacaramb, and Caraci. Around the Gold Polygon there were simple strands and networks of strands. Native gold could be found in sulphide-impregnated nests, as well as sheet-like, plates, wires or crystals 3-4 mm long, associated with pyrite, blend, and galena or other minerals such as quartz or calcite. The gold strands in this area run up to 500 m deep and 800-1,000 m long. The gold concentration was variable, ranging from 1.0 g Au/ton ore up to 5.0 g Au/ton ore.

In Transylvania, the Roman rule meant intense gold mining. After the Roman retreat, for almost 1,000 years there was a decline in gold exploitation. The beginning of the 14th century is also the new start of systematic exploitation in Apuseni and Maramures. It is estimated that during the Middle Ages, gold exploitation in Ardeal resulted in approx. 450 kg/year; after the 1500s, production doubled and sometimes surpassed a ton/year. At the beginning of the 17th century, gold production in the mines from Maramures and Apuseni meant 20% of the world production. In the Habsburg period gold extraction increased greatly. After World War II, production began to drop steadily, from 7 tons in 1947, to 6 tons in 1960, 5 tons in 2000 and 2.5 tons in 2005. Since the beginning of the gold exploitation to date the amount of gold extracted in Romania is estimated at approx. 2,200 tons.

The Gold Museum

The Gold Museum in Brad began with a collection of gold rocks gathered by a German geologist about 1896 from the mines in Apuseni, and since then around 1,300 pieces of both native and world gold found a place in the showcases of the museum, which now hosts the largest collection in Europe.

The specific element of the museum is that the gold pieces are natural, none have been processed or altered, thus being jewels of nature, the result of the mysterious production “technology” of the mountains’ deep, unrelated to human aesthetic rules. Gold processed and cast in decorative shapes is, in fact, subjected to the vanities and ambitions of the one who uses it to display power, wealth or sacerdotal distinction. We need to differentiate between the “wild”, “raw” gold we see at the museum in Brad and the “civilized” gold we may see in the different museums around the world, as helmets, bracelets, jewelry, utensils, in commercial use. “Civilized” gold is, in symbolism and utility, man’s servant, whereas “wild” gold inherits the innocence of a nature untouched by man’s interests.

The collection in Brad highlights gold in its mineral formations in the form of pulses, pure or concocted with other minerals – in combinations with tellurium (a rare silver semi-metal, discovered in 1782 in the mines in Zlatna), with sylvanite and nagyagite-, as lamellae, filaments, dendrites, granules, phytomorphs, zoomorphs or forms that mimic artifacts (a cannon, a Dacian flag). 800 of the museum’s pieces come from other countries. The Romanian pieces are brought from Rosia Montana, Baita, Baia-Mare, Brad, Cavnic, and Baia Sprie.

The pieces originating from the Gold Polygon stand apart because of their shape and size, and are the most spectacular from the entire collection: the Dacian flag, the pentagonal crystal, which is unique in the world, the lamellar gold called “Pana lui Eminescu”, the gold lamellae called “Feriga”, the mini-lamellae called “Soparla”, the lamellar gold with crystal deposits.

The historical image of Transylvania has always been associated with gold, which is one the many valuable resources of this space, together with its mineral waters, the salt, the forests, the wines and vineyards, the impressive mountains, the gentle slopes grazed by centuries old fairs, villages, and hamlets. The galleries in Rosia Montana no longer have gold now, but they possess something equally valuable – gold’s memory and mythology in this space. When gold runs out or is taken from the place where it was formed and sat for thousands of years, the empty space needs to be filled with intelligence and creativity, so as not to become deserted.

By Vianu MUREȘAN

(From the special edition of TB 86 – „ENJOY TRANSYLVANIA!” – May/June 2019)