Some of the largest salt resources in Europe have been found in Transylvania, and they have been exploited since ancient times, in the Roman era. Underground salt layers are widespread and they measure 400-500 metres, at varying depths. The former mines are located in places where salt was closest to the surface and therefore easier to identify and exploit. Recent measurements show that the salt works in Turda, for instance, are situated on a 1,200-metre-thick mushroom-shaped salt layer.

History

The first records related to the salt trade date from 892 a.d., in a document chronicling how the King of the Franks pressed the Bulgarian Khan, which then ruled the Transylvanian territories, not to allow the sale of salt in Moravia. Since the 11th century, after Transylvania becomes part of the Hungarian Kingdom, the salt mines became the property of kings, masters of the conquered territories, and salt trade soon became the second source of revenue in the royal treasury. The kingdom’s largest salt works were in Transylvania – Turda, Dej, Sic, Cojocna, Ocna Sibiului, and Maramureş – at Coştiui and Rona.

In the 11th-13th centuries, royal salt storehouses were supplied from the mines of Transylvania. Their administrators were usually Muslims or Jews. Some of the salt in these storehouses was given to the Church, which also had the right to sell it. A 13th century document, the Berg agreement between the King and the Church in 1233, shows the amount of salt ceded by the King to the 29 dioceses, namely 143,000 pieces of salt. They were roughly standardised, weighed about 8-10 kg each, were cut out of larger blocks and shaped in the salt works.

In order to increase both the efficiency of the salt trade and profits, salt depots were set up in 1397 and managed from the capital – a system remaining until the installation of the Habsburg in Transylvania, at the end of the 17th century. Such depots were built in Turda and Ocna Sibiului (1) (each of them supplied by five salt mines), Dej and Cojocna (each supplied by three salt mines), Sic (supplied by two salt mines), and another depot in Maramureş. In the 18th century, the salt depots were reorganised into salt offices. They were centralised, subordinated to a bureau with authority over all the Transylvanian salt works, led by a ‘director rei salinarie’, a ‘perceptor salis (2)’ and a supervisor.

The methods of exploitation practiced in Transylvania were different from those of the Romans, who preferred quarry-type works. The Romans cut the salt from the surface downward, in descending layers, digging quadrilateral pits down to about 15 meters. In the Middle Ages, salt mines had the shape of a bell, cone or arch. First, they made a perpendicular shaft for the miners to descend through to the salt level, after which the quarry work actually began. After each excavated layer, the descent to the next would be wider in a circular area, so that the top remained a rounded wall in the arch. The large blocks of salt were cut with wood wedges and chisels, hammered, and then further carved with pickaxes and shaped to standard sizes – approximate cubes of about 8-10 kilograms each to be transported on land and 3-5 kg pieces to be transported on ships or barges. According to the surviving documents dating back to 1515, about 2,537,916 cubes of salt were produced in Transylvanian quarries, and in 1533 about 1,430,525 cubes. Around 1530, the total salt production in Transylvania was estimated at 1.7 million pieces, or 11,000 tonnes.

Salt cutters were led by a master, which was responsible for mine work and represented them in relations with the authorities. There is documented evidence that in the sixteenth century there were about 40 to 70 salt cutters for each storehouse, indicating around 300 workers at the mines in Transylvania. They were paid according to the amount of salt cut: about 20 dinars per 100 pieces of salt in the first half of the 16th century in Transylvania. Remuneration was however different from mine to mine. For the major holidays – Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, All Saints’ Day – salt cutters received an extra 100 loaves of bread, a barrel of wine and an ox. Workers in Turda, for instance, received „incentives” almost every Sunday or holiday, consisting of a barrel of wine, an ox or sheep. Besides, salt cutters were described by the chroniclers of the time as sullen, inveterate and unbridled drinkers.

After being excavated, salt was deposited on the surface or, later, in warehouses, pending transportation to various destinations in the kingdom. The largest transports were made on the rivers Someş (from the Dej salt mines) and Mureş (from the Durgău-Turda mines) to the Tisa confluence and further on the Danube. A boat about 10 meters long and 5 meters wide could carry about 60 tonnes of salt. There were about two series of transports each year by boats, beginning in the spring, after Easter, when waters would rise. The Turda-Lipova route, by boat, took about a week.

Proceeds from the salt trade were the second source of revenue for the kingdom’s treasury, after taxes. During the reign of King Bella III, between 1172-1196, the royal treasury earned 16,000 silver marks annually from the salt sale; this accounted for 7% of the total treasury budget. In the days Sigismund of Luxemburg, the income would be about 100,000 florins annually. Under Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490) (3), 13% of the central budget was secured by salt trade.

For a better understanding of the importance of salt both as a resource in the kingdom and in the life of the Transylvanian communities, we should add that the Church received significant quantities of salt from the royal warehouses, the noble families were provided with the necessary salt for household needs throughout the entire year, the Transylvanian Saxons and the inhabitants of the salt areas were allowed to extract salt for one week each year without paying it, the border guards on the southern border of the kingdom and many royal dignitaries received a portion of their income in salt. According to old records, in 1504 the soldiers received salt valued at 20,588 florins (18% of their total pay), and in 1511 the quantity of salt given to them was valued at 21,484 florins (15% of their total pay).

So as far as we know, salt was not only food and commodity but also „currency” in the Middle Ages.

The Salt Mines today

Some of the former salt mines have collapsed after they were abandoned. Others, on the other hand, were rehabilitated and introduced into the touristic circuit. The Durgău-Turda salt works has been exploited ever since the Romans had a fort at Potaissa (4). After Romans withdrew from Dacia, in 274 A.D., it is not clear whether or how salt exploitation was continued. The oldest preserved document to mention the Turda Salt mine was issued by the Hungarian Chancellery in 1075 and refers to the customs of the Turda salt works. In an official document from 1271 there is an extremely valuable information: the salt works of Turda were gifted to the head of the Transylvanian Episcopate, which back then had its headquarters in Alba Iulia. Throughout the medieval period, until the administrative takeover by the Habsburgs, four underground mines operated: Katalin, Horizont (Nagydörgö, Durgăul Mare), Felsö-Akna (Ocna de Sus), Karoline (Carolina), and Joseph.

Under Austrian rule, the economy and administration of Transylvania were reorganized and the exploitation of salt, a reliable and important source of profit, was highly dynamic. As a result, in the 17th-19th centuries, another 5 underground mines were opened in Turda: Terezia, Anton, Cojocneană (Kolozser), Rudolf and Ghizela. The Terezia, Anton and Cojocneană mines, opened in 1690, were bell-shaped, while the other two were trapeze-shaped, which meant a modernization of salt exploitation. The Franz Josef (5) access gallery was excavated between 1853 and 1870, in order to facilitate the transport of salt to the surface, and was 780 metres long. At the end of the 19th century it was extended by another 317 meters. Today, 850 meters of the Franz Josef gallery are accessible for tourists.

In 1932, saltworks in the Turda mines were permanently stopped due to lack of efficiency and obsolete equipment. In the Second World War, the mine served as refuge for the population during bombings. Since the 1950s, the locals have used half of the Franz Josef gallery as cheese storage space (6). In 1992 they were reopened, but for health and tourist destinations.

In 2008, the salt mine went through a major modernization project within the PHARE 2005 CES large regional / local infrastructure programme, amounting to 6 million euros. It was reopened in January 2010. The Turda galleries were spectacularly rehabilitated and have become, shortly after the official opening, one of the main tourist attractions in Europe. A panorama lift, a mini-golf course, two mini-bowling tracks, a sports field, a 180-seats amphitheatre, a carousel and a children’s playground were built in the Rudolf Mine. The underground lake in the Terezia mine, 112-metre-deep, can be enjoyed in a boat ride. The Ghizela mine has been transformed to serve the needs of spa treatments. The medieval mining instruments, the crivac (7) and the salt mill here are unique in Europe. You can also see the Altar, carved into a salt wall, and the Staircase of the Rich. In 2015, the Turda mine was included on the Ministry of Culture’s list of historical monuments in Cluj county.

Today’s resort of Ocna (8) Sibiului lies on a massive salt layer over a kilometre deep; it was one of Transylvania’s salt works to be almost continuously operated since the Roman period until 1931 – when the last active gallery, St. Ignat, was closed. In the Antiquity, salt from Dacia reached the farthest corners of the Roman Empire. Centuries later in 1780, Johann Fichtel (9) recorded activity in four different mines of various ages and sizes: Ocna Mare, with a depth of 124 m and a base perimeter of 200 m, Ocna Mică, with a depth of 110 m and a basin of 169 m, Ocna Sf. Nepomuk, with a depth of 34 m and a base perimeter of 36 m. Back then, Ocna Sf. Iosif barely began its activity.

The centuries-long exploitation and extension of excavations have led to land collapses and salt lakes in the area: Horea, Cloşca, Crişan, Panzelor-Inului (Iosif Mine), Bottomless Lake (Francisc Mine), Avram Iancu (Ocna Mare, the deepest anthropogenic lake in Romania with a depth of 132.5 m), Ocnița (Ocna Mică), Sf. Ion (Sf. Ion Mine), Poporului, Dulce, Brâncoveanu, Mâțelor, Vrăjitoarelor, Sf. Ignat, Trestiilor, Austel. The so-called Bottomless Lake (Romanian: Lacul fără fund), 34.5 meters deep, is like a funnel filled with brine and was formed in 1775 when the Francisc mine crashed; today it is a natural reservation.

The salt lakes of Ocna Sibiului have certain particular properties – their stratification, salinity, temperature – due to the conditions that generated them. On their surface there is a layer of fresh water; the deeper the water the saltier it gets, but this saline concentration traps a lot of heat that keeps a constantly warm temperature in the lake. There is a permanent thermal spa here, with both a treatment area and a recreational one. The natural aerosol-rich air, the temperature well above the average in this part of the country due to accumulations in the salty lakes, the renovation works of the swimming pool made the resort attractive again for balneotherapy tourism enthusiasts.

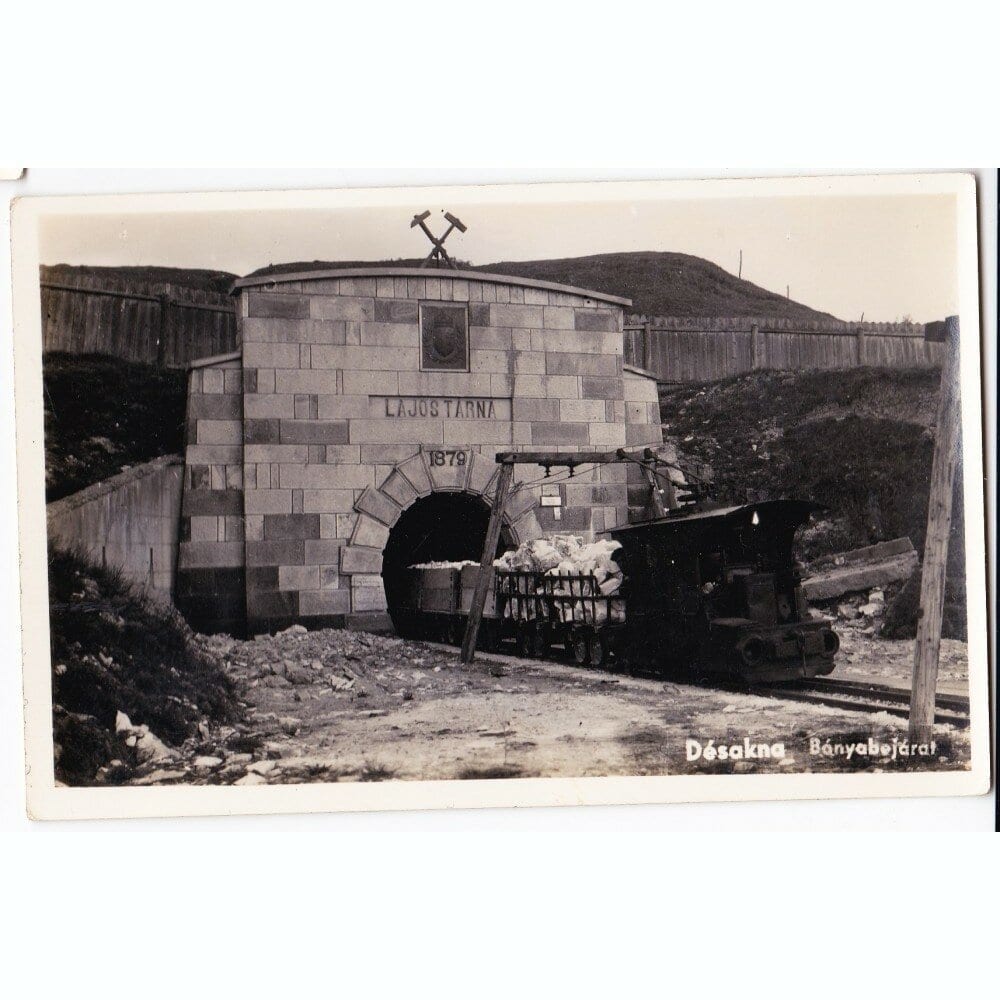

The Ocna Dejului salt mine is one of the most active and exploited salt mines in Transylvania throughout the medieval period. Activities in the galleries here and in Turda were facilitated by the transport infrastructure in the region, on the nearby Someș river. The Roman fort in Gherla controlled the salt mines in Dej, Sic, Cojocna and Pata during the Roman period.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the salt mines of Dej had the usual bell, conical or arch shape. In 1780 there were two ogive mines of salt we have data about: the Iosif mine, with a depth of 63 metres and a base perimeter of 129 metres; the Ștefan mine, with a depth of 42 metres and 67 metres of basal perimeter. Over the years, the following mines have also been active here: Mare, Ciciri, Ferdinand (renamed 23 August), May 1st, and, since 1979, the Transilvania mine. The latter is the only one active today. Some of the former galleries collapsed and salty lakes have formed, such as the Toroc-Cabdic Lake in the northern sector, and Iosif, Ștefan, the Mina Mare in the southern sector.

The Praid salt mine, in Harghita county, is part of the Dealul Sării complex, together with Ocna de Jos and Ocna de Sus. The underground salt layer has been recently measured at 2.6-2.8 kilometers thick, the biggest in Romania. Volker Wollmann, in a monographic work on mining in Transylvania, associates the strategic and economic importance of salt mines with the construction of Roman forts. The Praid mine, for instance, was defended by the Praetoria Augusta fort in Inlănceni. Although known ever since Roman times, and there are notes about certain mining activities here from 1200, it was only after the establishment of the Austrian administration that the massive mining operations at the Praid mine began. The first gallery was opened in 1762, bell-shaped, and was named Iosif (Jozsef). Two branched galleries followed, Carol and Ferdinand. Along with the underground exploitation, there were also surface quarries from which salt was extracted.

In 1787, the salt at Praid becomes the property of the Austrian state. A second underground gallery was excavated in 1864, not far from the Iosif mine. It was named the Parallel (Párhuzamos) salt works, trapezoidal in shape. Due to the expansion of the works, it grew into one of the largest underground excavations in the country – any Gothic cathedral in Romania could fit inside. In 1898, work started on a research gallery on the north-eastern side of Dealul Sării, called Elisabeta, from which several lateral branches were opened in order to study the deposits. The gallery named after Gheorghe Doja (10) was opened after the Second World War, in 1947-1949, to transport salt to the surface. The last gallery, called Telegdy (after Telegdy Károly, a former director of the mine) was opened in 1991 and commissioned in 1994; the so-called „Canadian” exploitation method was applied here, on square pillars with a 14-metre front.

The Praid mine has been available for tourists for four decades and is also visited for its health benefits. Speleo-therapy and climato-therapy consist of inhalation the salty air, with great results in case of respiratory diseases (asthmatic, bronchial and allergic). The average duration of the treatment is two and a half weeks and is organised the sanatorium situated on the so-called horizon „50”, at a depth of 120 metres, under constant medical supervision. The renowned treatment programmes and their efficiency in the salt mine air have made the numbers of European tourists attracted here to steadily increase, averaging around 200,000 per year.

Besides the economic and commercial aspects, besides being a basic ingredient in food and treatment in various ways (baths, aerosols, inhalations, scrubs, purges etc.), salt is culturally linked to the history of Transylvania, it has entered into folklore, music, folk literature, and has been used in many types of rituals, magical practices, enchantments and traditional medicine. Daily life in Transylvanian villages and cities would be hard to conceive without salt, because it was the main food preservation medium, both solid and liquid – such as brine. The preservation of meat and slană (11), the true culinary brand of Transylvania; cheeses – the archetypal food for a people so much linked to the pastoral life; pickles and so many others – these would be unthinkable without salt. It has become the cultural expression of „good” that accompanies us in our transition through life. That “good”, with significance beyond matter and taste, is „salt-in-food*12”.

(1) – Ocna Sibiului is a town nearby Sibiu, one of the most important Transylvanian cities. Its very name, ‘Ocna Sibiului’, actually means ‘the saltworks of Sibiu’.

(2) – director rei salinarie (Lat.) – director of saltworks. perceptor salis (Lat.) – a person collecting either taxes or a percentage of production. The naming of administrative functions in Latin was common in several parts of Eastern Europe at the time.

(3) – Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I (Hungarian: Hunyadi Mátyás, Croatian: Matija Korvin, Romanian: Matei Corvin, Slovak: Matej Korvín, Czech: Matyáš Korvín) was one of the most important kings of Hungary; he ruled overs territories that are now in Romania, Croatia, Bosnia and other Eastern countries. He was also a patron of the arts and among the first non-Italian monarchs to promote the Renaissance. (Wikipedia)

(4) – The Roman name of the settlement that grew into the town now known as Turda, in central-western Romania.

(5) – Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (Franz Joseph Karl; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and monarch of many other states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, from 2 December 1848 to his death. From 1 May 1850 to 24 August 1866 he was also President of the German Confederation. He was the longest-reigning Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, as well as the third-longest-reigning monarch of any country in European history, after Louis XIV of France and Johann II of Liechtenstein. (Wikipedia)

(6) – Salt galleries make exceptional storage spaces due to their preserving properties. Several such spaces are used throughout Transylvania; the cheeses and hams thus matured are considered delicacies.

(7) – A medieval installation, man or horse-driven, serving as a sort of „salt elevator”.

(8) – ‘Ocna’ is an old Romanian word for mine, prison or site for hard labour.

(9) – Johann Ehrenreich Fichtel (1732 – 1795), counsellor for Transylvanian rulers, author of several works on Carpathian mineralogy.

(10) – Gheorghe Doja (Hungarian: Makfalvai Dózsa György), 1470 – 1514. Petty Szekler nobleman who led a huge grass-roots revolt in 1514, a peasant war against Hungarian land-owners.

(11) – Slană or slănină, a type of boiled, cured or dried lard.

(12) – An expression („To love someone like salt-in-food.”) coming from a famous Romanian folk tale, in which it means indissoluble, quintessential love and good.

(From the special edition of TB 86 – „ENJOY TRANSYLVANIA!” – May/June 2019)